A popular malware scheme and pay-per-install services.

Dave Bittner: Hello, everyone. And welcome to the CyberWire's "Research Saturday." I'm Dave Bittner. And this is our weekly conversation with researchers and analysts tracking down threats and vulnerabilities, solving some of the hard problems of protecting ourselves in a rapidly evolving cyberspace. Thanks for joining us.

Michael DeBolt: We started looking at PrivateLoader back in August timeframe, 2021. We actually coined the name based on a tech strain we found in one of the first binaries the team was ripping apart that contained the word private loader in one of the file directory paths.

Dave Bittner: That's Michael DeBolt. He's chief intelligence officer at Intel 471. The research we're discussing today is titled "PrivateLoader The first step in many malware schemes."

Michael DeBolt: And since then, we've really just been tracking the evolution of the loader itself and the unidentified PPI service, which is a pay-per-install service that is connected to this PrivateLoader piece of malware. So the diversification of the different kind of malware that this thing is deploying and just the geographic spread of where we're seeing these victims has been quite something to track over the past few months.

Dave Bittner: Can you help us understand what we're talking about when we say pay-per-install malware services? What exactly does that represent?

Michael DeBolt: Yeah. So let's take a step back. PrivateLoader is a type of loader malware. Sometimes we call this a dropper malware. And its primary purpose is to install other malware payloads onto victim machines. So those other malware payloads could be anything from remote backdoors to banking Trojans, information stealers. We've even seen ransomware at times. So this PrivateLoader malware is connected to a pay-per-install service, which we've actually, interestingly enough, haven't been able to connect the PrivateLoader malware to any - to a known service in the underground. And we can touch on that if you want.

Dave Bittner: Yeah.

Michael DeBolt: But PPI services have been around for a very, very long time. They're typically advertised in underground forums. And they offer the convenience of outsourcing the distribution of malware in a very reliable and affordable way. So operators behind PPI services, they basically earn money by accumulating infected hosts - and we call those installs - and spreading malware samples supplied by paying clients. So clients come in. They typically - you know, they select which installs they want based on a number of installs, based on geographic location and a number of other variables. And like other enabling services that we see - like bulletproof hosting, for instance - PPI services are really important for the cybercrime ecosystem because if you think about it, over the years, us as security professionals, we've kind of made things increasingly harder and more difficult for malware operators to actually get their malware onto victims' machines. So these dedicated services, they offer a great way for actors to offload this burden so they can focus their time and energy on the actual profits from their payloads, whatever that might be.

Dave Bittner: Right. Now, the folks who are offering up these pay-per-install services, I mean, have they - do they have a collection of systems out there that they've already penetrated and are just waiting for them to pull the trigger and put, you know, your malware on there, you know, today?

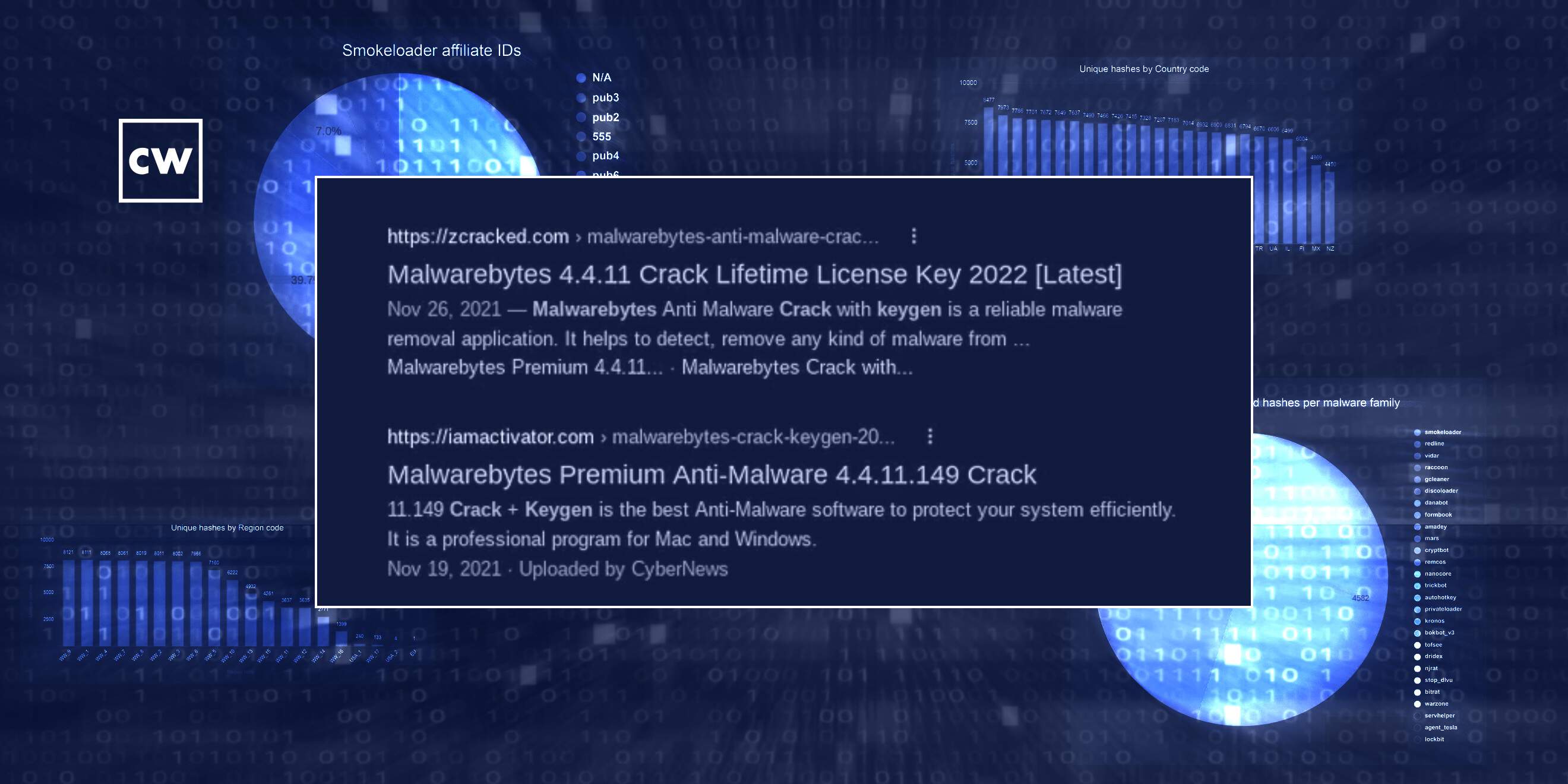

Michael DeBolt: They do have an inventory of pre - we'll just call them pre-infected installs that are sort of ready-made and off the shelf you can get. So the PrivateLoader malware is distributed through a network of fake websites that lure unsuspecting visitors to download cracked or pirated software. And the theme of the day for this group in particular is mostly around antivirus programs or privacy tools. So they use websites that have search engine optimization - or SEO - to appear at the top of the results page whenever users, you know, search for words like cracked program or cracked download or something similar. Visitor goes to one of those websites, they click on a download link, the embedded JavaScript makes a few redirects and eventually downloads this PrivateLoader payload from one of the backend servers that the operators manage. And that's typically in the form of a password-protected zip file.

Michael DeBolt: So then it gets on to the victim's machine, and the loader malware is either installed by itself or it may come with another payload from, say, a client who paid for that install. Hey, I want to drop also an information stealer or a banking trojan or even another loader like Smoke Loader, which is actually quite common in this case. And then, like you said, from there, once PrivateLoader is installed on the victim's machine, that victim becomes part of - we'll just call it the PPI services inventory and then the actors can manage it. They log into a web panel, kind of an administration panel where - it's basically a portal where clients can log in, they can manage their installs, they can upload their malware to be encrypted and delivered. There's the statistics page. It's actually quite professionalized and quite common to see this in the PPI space.

Dave Bittner: Do you have any sense for how much churn they have? In other words, you know, they prepare a system to later have something dropped on it. Do we have any idea for how persistent they're able to be, how long they're able to stay on those systems? Or are they noisy enough that they're getting detected and kicked out?

Michael DeBolt: Yeah, I don't have any statistics to back any of this up, but I would say this is more of a quantity game than a quality game, if that makes any sense. I mean, this is more about accumulating as many installs as possible to give your clients - in this case, malware operators that want to deploy their malware - as many options as possible around the world for them to choose which installs that they want to deploy their malware to at any given time. So it's - you know, I'd say the churn is pretty heavy. I mean, you're talking about - you know, the vast majority of what is deployed through these PPI services are highly commoditized malware. So the blocking and tackling of those particular types of malware is a little bit easier than, say, nation-state curated malware, where it becomes a little bit more challenging to identify and block those attacks. So I'd say the churn is a little bit more for PPI services to try to keep up their inventory. But, I mean, we're talking about, you know, many, many, many installs at any given time. They can withstand churn, if you will.

Dave Bittner: I see. One of the things that you all have tracked here in your research are the various malware families that get dropped here. Can you give us a little description of what's going on and what this indicates to you?

Michael DeBolt: It's interesting because on its face, there's nothing really that sets this PPI service apart from other similar services. In fact, most of the activity - and you'll see this in our blog - with the delivery mechanisms and the commodity malware that we're seeing a drop is kind of low- to mid-level stuff. But one notable thing that we - that did catch our attention and we noticed this in our blog as well is that PrivateLoader was used to drop some high level - high-profile malware, including Dridex and Trickbot and a couple others, in a very short time window. So that's interesting. We don't know yet if this indicates any sort of formal partnership between the PPI service provider and those more sophisticated crews. It could be some sort of affiliate arrangement or it could be that these crews are simply testing this new PrivateLoader PPI service as a new delivery mechanism. But it's definitely something to keep an eye on, as it would indicate - early indication, I would say - that this service is operating at a higher echelon of reputation and credibility by working with those more sophisticated malware families.

Dave Bittner: Now, you also noted that PrivateLoader embeds a region code in its communications with its C2 server. What does that represent, in your estimation?

Michael DeBolt: Sure. It's just another way for these PPI service providers to sort of categorize and offer clients who are coming in to select their installs another factor, another variable to which they can select installs that cater to the different types of malware that they're using. So, say, for instance, I'm a malware operator and I want to target banks within a certain region. I'm going to select installs within that region that I know victims are logging into a certain bank or a set of banks within that region that my malware is catered to, say, steal their login credentials, for instance. So it's just another way for PPI services to offer that as another feature within their service that actors can leverage for more targeted geographic attacks.

Dave Bittner: Do you have anything that indicates any sort of - you know, with any confidence, any attribution of who's behind this?

Michael DeBolt: Yeah, so that's the tricky part, right? Attribution is always the hardest thing to accomplish whenever we're doing cybercrime research. And I always like to say, just as a side note, we don't do attribution for attribution's sake. We want to do attribution to know who the actors are behind whatever the threat is, so that we can establish a pattern of, you know, how are they acting? What are the TTPs that we're likely to see? You know, we've seen with ransomware actors, for instance, them rebranding over and over and over again.

Michael DeBolt: Well, if you're chasing the brand names, it's harder to understand the TTPs if you feel like you're starting over from square one each time. Well, in reality, some of these actors are just rebranding. They're the same actors doing the same stuff. They're just rebranding. So that's just kind of a side note around attribution. We do have some - as it relates to this, I mean, we do have some indication of some of the actors that might be involved in developing this private loader malware and, in a sense, also connected with the unknown PPI service. I don't want to get too much into that right now just because it's kind of based on some sensitive methods that we're using and sources that we have. But I will say that we do, in all likelihood, expect that this PPI service will probably announce itself in the near time within the underground forums that we commonly see announce similar services.

Dave Bittner: Now, you point out that the most common payload you saw pushed by PrivateLoader was something called SmokeLoader. Anything noteworthy there?

Michael DeBolt: Yeah. I mean, loader pushing another loader, right? I mean, that's kind of what we're seeing here.

Dave Bittner: Right.

Michael DeBolt: You know, we've been tracking SmokeLoader for a long time. It's been on the scene since - I think since at least 2011, if I'm not mistaken. You know, it offers another layer of capability for actors who are using perhaps PrivateLoader for the initial delivery mechanism, but then landing SmokeLoader on an install. And SmokeLoader is very modular. So it has, in addition to its loading capabilities, it also has a number of different functionality that can be added on, password stealing. It could even do DDoS, cryptocurrency mining. So it's very flexible, and it can be very persistent. So it's really no surprise to us to see that at the top of the list as kind of the top malware family that we're seeing pushed through this PrivateLoader malware.

Dave Bittner: You know, typically I will, you know, ask my guests what their recommendations are for people to protect themselves against this thing. But I guess it's fair to say No. 1 is don't download cracked software.

Michael DeBolt: Yeah. I think that's a pretty glaring takeaway here. Yeah. I think you're right. I mean, these are pretty straightforward security operations, you know, tracking commodity malware. You know, the biggest thing is, you know, you want to protect against - this is going to sound obvious, right? - but you want to protect against being a victim of a PPI installation. You don't want to be - you know, you don't want any of your employee workstations to become part of this inventory that sort of bad guys can pick and choose from to deploy whatever malware they want to.

Dave Bittner: Right.

Michael DeBolt: You know, it requires regularly monitoring the underground for these new PPI services and the associated loader malware that's connected to them, you know, understand their backend infrastructure, the delivery mechanisms. You know, like you said, searching for or installing cracked software, that's a big no-no. So maybe we can use that as, you know, employee awareness and training material - right? - to get them to understand the actual ramifications of what they're doing.

Dave Bittner: Right. Right. If you find yourself at the point where you feel like you need to buy cracked antivirus software, please speak to the security team, and we will do our best to get that funded for you. Right? (Laughter).

Michael DeBolt: And it's interesting because we're, you know, with the whole COVID pandemic thing over the past two or three years or whatever it is now, we've seen with, you know, remote working, you know, everybody, you know, going home and working and bringing your own device and all this stuff. I mean, it's not out of the realm of, you know, increased possibility and probability that you would see employees, well-intentioned employees trying to, you know, secure their home laptop - right? - and going out and doing it on their own. So it's definitely something to keep in mind.

Dave Bittner: Our thanks to Michael DeBolt from Intel 471 for joining us. The research is titled "PrivateLoader: The First Step in Many Malware Schemes." We'll have a link in the show notes.

Dave Bittner: The CyberWire "Research Saturday" is proudly produced in Maryland out of the startup studios of DataTribe, where they're co-building the next generation of cybersecurity teams and technologies. Our amazing CyberWire team is Liz Irvin, Elliott Peltzman, Tre Hester, Brandon Karpf, Eliana White, Puru Prakash, Justin Sabie, Tim Nodar, Joe Carrigan, Carole Theriault, Ben Yelin, Nick Veliky, Gina Johnson, Bennett Moe, Chris Russell, John Petrik, Jennifer Eiben, Rick Howard, Peter Kilpe. And I'm Dave Bittner. Thanks for listening. We'll see you back here next week.